Welcome back!

Now you have carried out the experiment on the chromatography of leaf pigments and can certainly answer the following questions.

If you couldn’t do the experiment, look at the results photos at the bottom of this page and then try to answer the questions.

In the experiment with isopropanol as the mobile phase, the green leaf pigment extract separated into its components. The components are more or less clearly visible as stripes.

An extract (from Latin ‘extrahere’ = to pull out) is a (plant) substance that is extracted from a mixture of substances using a solvent.

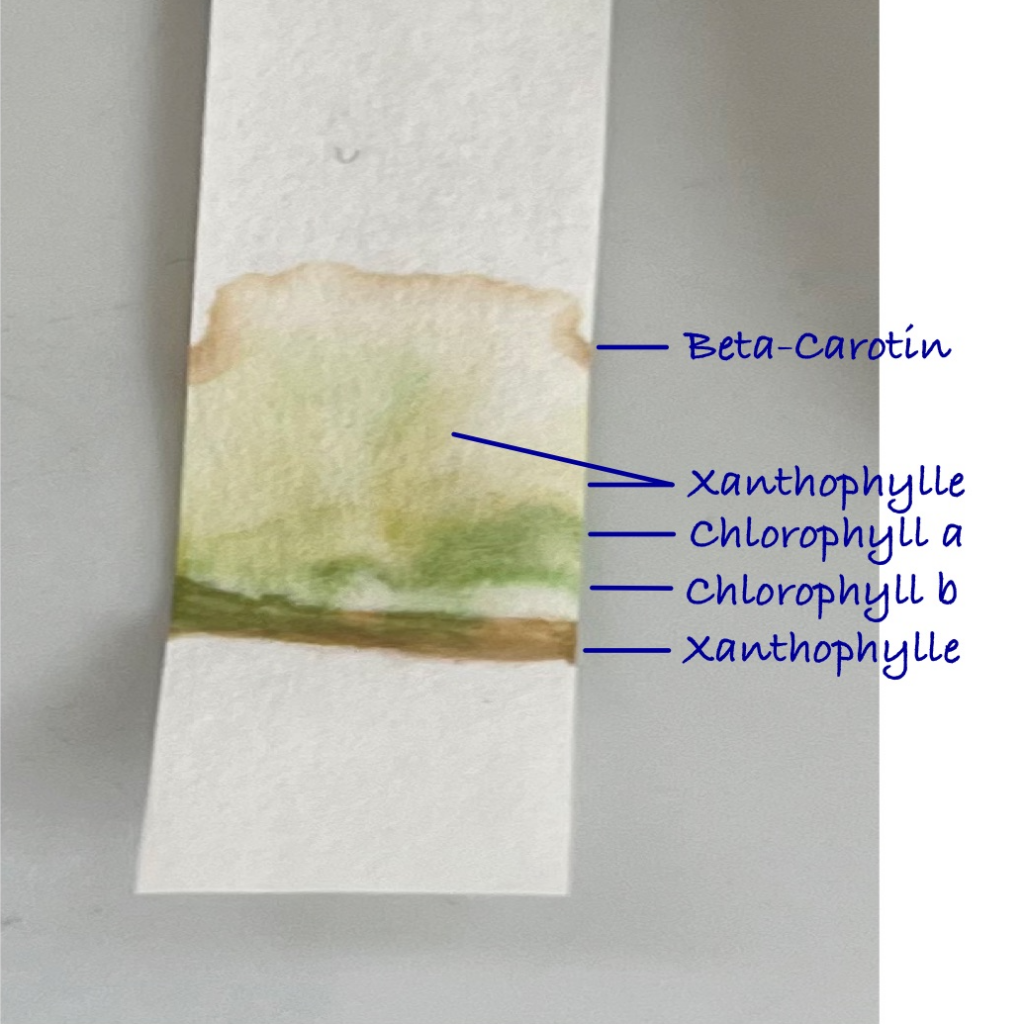

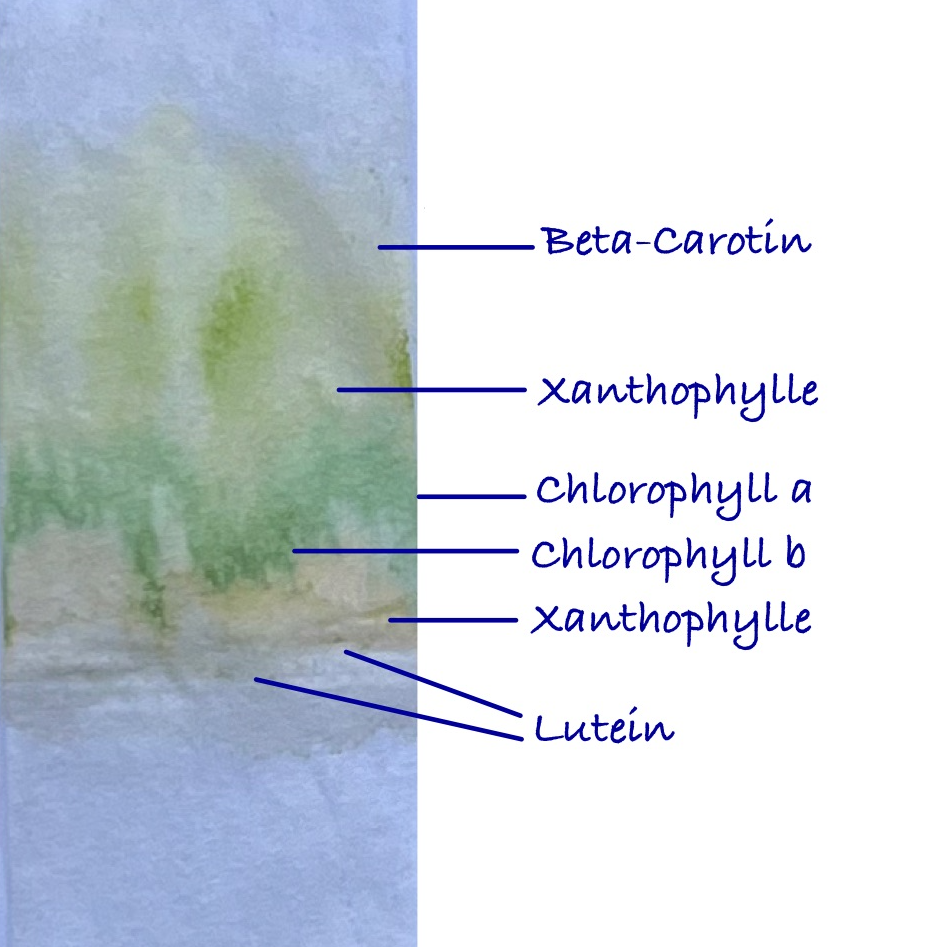

This is what the chromatograms of chromatography with extracts from spinach leaves and with extracts from lilac leaves look like:

When using isopropanol as a solvent, it becomes clear: Spinach leaves contain chlorophyll (green), carotenoids (yellow-orange), and xanthophylls (red-orange-yellow).

With isopropanol as the mobile phase, it also becomes clear: In addition to chlorophyll (green), carotenoids (yellow-orange), and xanthophylls (red-orange-yellow), summer lilac leaves also contain luteins (orange).

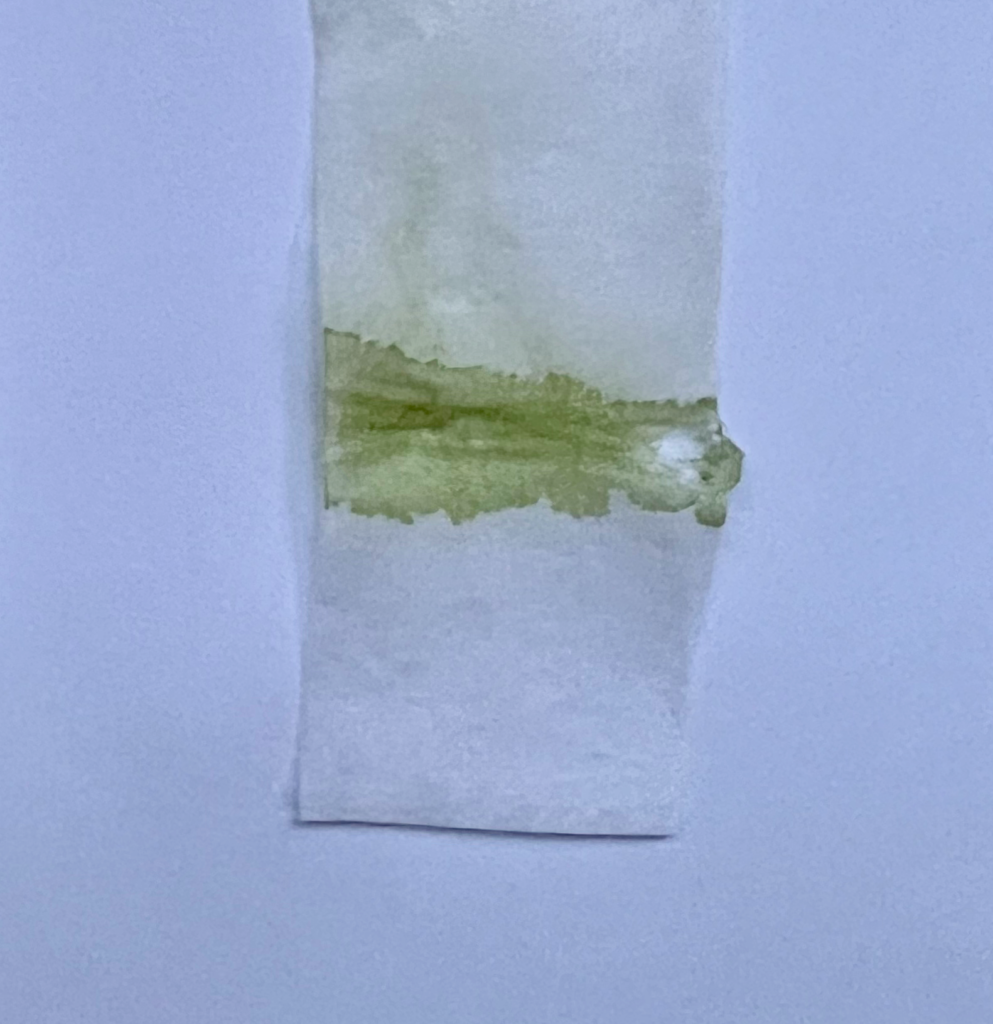

If we use water as the mobile phase, the leaf pigment does not separate, and we only get one (green) stripe.

Which leaf pigments are present in green leaves?

In the experiment, we saw that leaves contain not only green pigments but also yellow and orange pigments, which we cannot see in spring and summer. So how do the other pigments appear in autumn?

Plants need their green pigments not only to look pretty – the green pigment chlorophyll plays a crucial role in photosynthesis.

During photosynthesis, plants convert carbon dioxide from the air and water into oxygen and glucose. Chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, the green pigments in leaves, help to bind carbon dioxide in the cell. In autumn, temperatures drop and there is less light, so the tree reduces photosynthesis.

Furthermore, as it gets colder, trees break down chlorophyll and store it in their trunk, branches, and roots until spring.

In addition to chlorophyll, there are other pigments in the leaf – but not all leaves contain the same amount of different pigments, which is why the leaves of different plants also look different in spring and summer.

Leaves get their color from leaf pigments: color pigments such as chlorophyll, xanthins (a xanthophyll), lutein (a carotenoid), and phaeophytin. The color pigments reflect light – chlorophyll, for example, reflects green light, which is why leaves with a lot of chlorophyll appear green.

The less chlorophyll (green) the leaves contain in autumn, the more the other pigments present in the leaves become visible: carotenoids (orange/yellow) and xanthophylls (red/orange/yellow) cause the leaves to change color to yellow and red.

The existence of leaf pigments other than chlorophyll was discovered more than a hundred years ago by a Russian scientist, whom you already heard about in the introduction to chromatography:

“Green is not just Green”:

In 1903, the Russian botanist Mikhail Semyonovich Tsvet discovered that the green leaf pigment chlorophyll is not just one green color but consists of several colors.

Tsvet dissolved a chlorophyll extract in ligroin (petroleum ether) and filled the mixture into a glass tube filled with inulin sugar. He then slowly let the liquid drain out of the bottom of the glass tube and poured in ligroin as the mobile phase. The green chlorophyll extract separated into blue-green chlorophyll a and yellow-green chlorophyll b. Later, Tsvet also chromatographically separated the other leaf pigments.